The emphasis is on the counterparties rather than on the credit institutions because it is their spending and saving decisions which infl uence economic developments. For this purpose, the focus of interest is the total amount of their monetary liabilities and credit extended, who holds the money, and who borrows from them. And, since our well-being underpins our collective resilience, and thus our ability to effectively respond to rapid societal changes, in the current context this assessment becomes not just desirable, but critical.įi nancial institutions 8 is to support monetary policy analysis and trace the transmission of monetary policy actions to the economy. Paying direct attention to the well-being of populations is the only way in which societies can truly assess whether the lives of their members are going well, or badly. As we all face up to the reality of an increasingly turbulent future, one where GDP growth may simply not be an option, the need to focus policy on the things that really matter – achieving well-being within the limits set by the Earth’s resources – becomes ever more pressing.

Facilitated by a fiscal system that has been allowed to operate with very few checks and balances, the focus on ‘growth at any cost’ created the giant credit bubble whose collapse has led to the recent global financial turmoil. In the process we have also squeezed the time and space we allow ourselves for pursuit of all the other activities which we know promote positive well-being and human flourishing. But a myopic obsession with growing the economy has meant that we have tended to ignore the negative well-being implications of the longer working hours and rising levels of indebtedness which it has entailed.

It is clear that economic measures can only ever be a limited proxy for the richness of our lived experience. Why we need National Accounts of Well-being

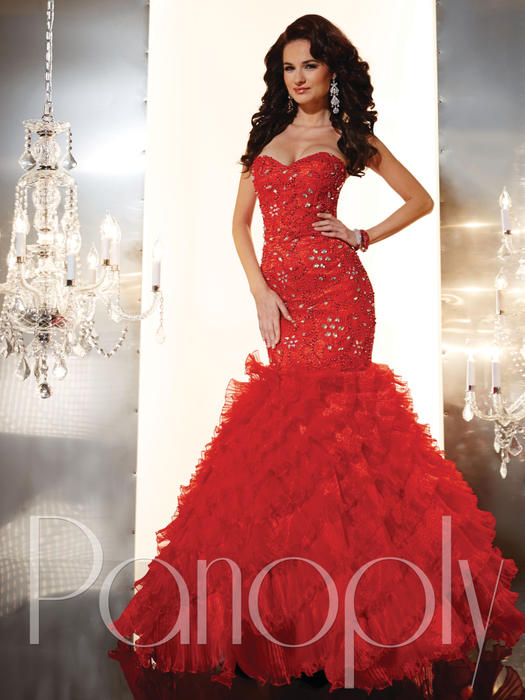

PANOPLY 44263 SERIES

The two series that exist for England/Britain, by Clark (2010) and Broadberry, Campbell, Klein, Overton, 8 Edvinsson (2005) Krantz and Schön (2007). In their GDP series for Holland 1500–1800, van Leuwen and van Zanden (2009) use rent as an indicator of annual movements in agricultural production, even though they present direct evidence of the annual movements of other activities. The demand approach is also applied by Schön and Krantz (2012) for Sweden for the early modern period.

Agricultural produc- tion is accordingly calculated from the development of real wages and real prices of agricultural and non-agricultural products.

Consumer theory requires that own price, income, and cross-price elasticities of demand add up to zero. 13), based on positing a demand curve for agricultural products. The demand approach was originally developed by Allen (2001, p. For example, Malanima (2009) presents annual estimates for Italy back to 1300 and Álvarez-Nogal and Prados de la Escosura (2011) for Spain back to 1270 in both cases, the so-called demand approach is used to calculate agricultural output, while other activities are approximated from the rate of urbanisation. However, with the exceptions of Holland and England, most of these approxima- tions are not based on direct empirical evidence concerning the actual output of various activities.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)